Diskurs

Deutsch in Kisten

Während Blob-Architektur sich in Deutschland auf besonders repräsentative Projekte beschränkt, bleibt die Kiste der Deutschen liebste Architekturform. Zumeist der Ökonomisierung von Finanzmitteln, Energie und Raum geschuldet, verhindern fünf Prinzipien den Ausbruch der totalen Langeweile. 1. Wie in der gelb verkleideten Erweiterung der Jugendherberge in Bremen (Architekten: Raumzeit) und im renovierten Apartmentgebäude Bogenallee 10–12 in Hamburg von Blauraum wird das Thema Kubus auf sich selbst reduziert. 2. Das ist manchen nicht genug. Ein gutes Beispiel dafür ist das Gebäude in Kemnat bei Stuttgart (siehe db 5/06, Seite 16), in dem Hans Klumpp Jugendzentrum und Leihbücherei verbinden konnte: Von der Box ist nicht viel übrig, die Ecken wurden abgeschnitten, die kubische Form verzerrt. 3. Eine weitere Strategie ist die Veredelung des Innenraums durch Licht und Leere, am besten umgesetzt im Kirchenzentrum München-Riem von Florian Nagler (siehe db 6/06, Seite 54). 4. Kraftvoll ist die Erweiterung mit Namen Pueblo-Haus, die Matthias Schmalohr in Oelde um ein typisches Siedlungshaus gelegt hat. Der rosa Kubus ist kunst-volle Architektur, da sich seine Fassade in ein abstraktes Spiel von geschlossenen und offenen (scheinbar ohne Innenbezug) Flächen verwandelt und der gleichfarbige Carport auf der anderen Seite das alte Haus in Pop-Art-Manier zitiert. 5. Auch durch das Material soll sich die Kiste auflösen, so im Stuttgarter Kunstmuseum, das von Glas umhüllt ist, oder im Jüdischen Zentrum in München, wo sich die scheinbar fest gefügte Basis bei näherem Hinsehen in eine lockere Aufeinanderschichtung grob behauener Steine verwandelt. Warum die Kiste so beliebt ist, darüber kann man spekulieren. In jedem Fall steht sie für einen neuen Realismus, der das Hier und Jetzt fixiert – aus dem in Zukunft noch Besseres entstehen könnte.

~Aaron Betsky

The Five Principles of the German Box

Like most countries today, Germany is torn between expressive icons and simple forms. The Dutch architect Ben van Berkel once said that he wanted to design buildings »between boxes and blobs.« Yet the temptation of the blob, which is to say the fluid forms computers can plot out and modern construction technologies can realize, has shown itself to be a somewhat stronger influence on his work, as evidenced the 2006 Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart. That temple to automotive form found an answer this past year in the BMW Welt in Munich. Together with some other large-scale structures that have been (more or less) finished recently, such as the new train station in Berlin and the Allianz Arena in Munich, the tone would appear to have been set for the total victory of the blob. Yet this is only true for such massive and highly iconic objects. At the scale of the community and the home, the place where most people might encounter architecture, the box has proven itself in the last year to be German architecture’s favorite form.

Like the Mercedes-Benz, BMW and Allianz projects, some of the best boxes this last year were designed by foreigners such as SANAA (the Zollverein School of Management and Design in Essen) and David Chipperfield (the Marbach Literature Museum, for which he won the Stirling Prize). These are extreme boxes, radical in their abstraction or refinement. But at a smaller scale, German architects are using the box to create simple, polite structures. The question is whether they can meet the blobs’ expressive power with their understated and recessive forms, or whether this is an architecture of reaction.

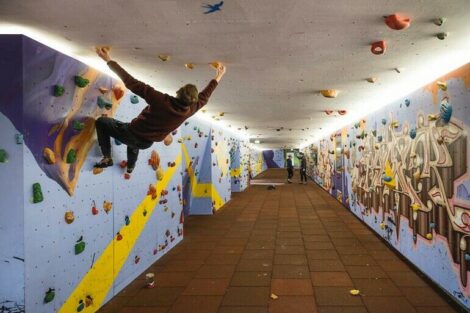

Certainly much of the breaking out of the box (or rather, its breaking in) is the result of economic restraints. When Raumzeit received the commission to renovate an old hotel in Bremen as a youth hostel, they could do not much more than restore and simplify. They chose to play a skin game, cladding the building with a yellow glass façade while opening up light-filled spaces inside where they could. Similarly, Blauraum in Hamburg reclad an old apartment building, but then pushed boxes out of one of the project’s long faces, creating a façade that is a kind of meta-box. Thus the most successful boxes, and this is rule number one, express themselves as such. They drink in existing conditions and give back a clarified version of those surroundings in an efficient manner.

The second rule of contemporary German boxes is that this is not enough. They have to question their own box-ness. The house and offices Allmann Sattler Wappner designed for themselves in Munich is in part a renovation of a historic structure that presents itself with a white stucco façade with shifting windows. The library and youth center Hans Klumpp designed in Kemnat is a good example of the same strategy. That seems a hallmark of many of the new boxes: façades that try to break down the edges and distort their basic form. It seems to be the second rule of building a box: break it, but gently, and only on the edges. The shifts bring down the scale, create variety, can make what is essentially a neutral form responsive to local conditions, and will let light in while allowing views out in unexpected ways.

The third rule is to hallow the box with light and sanctify it with emptiness. This strategy works especially well if one is designing a church, as Florian Nagler did in Munich-Riem. The outside of this concrete box is clad with white brick, the inside has no angles, no soft surfaces and nothing other than some luscious translucent windows to detract one from the spiritual beauty of pure forms in light – though the Catholics in this double church get a more luxurious version of that almost nothing. It is here that the German boxes ally themselves with a larger movement in dense minimalism, whose bible is Andreas and Ilka Ruby’s 2003 collection of such forms. In this architecture, everything is brought down to the point where it is not quite nothing, but a very refined and expensive something: a few lines, frames and dimly present shapes that attempt to remind us of architecture even as it seems to disappear.

But Germany also has a more forceful form of box making, exemplified by the Pueblo House in Oelde, by Matthias Schmalohr. The architect had this concrete addition to a classic, white stucco-clad gabled suburban house colored in a dusty pink (hence the name). In this manner he underscored the sculptural qualities of the block, something he made even clearer by carving oversized windows into its façades apparently not according to interior needs (though they do correspond to various spaces), but so as to produce an abstract play of solid and void. A carport on the existing house’s other side continues this game, making the original dwelling seem like a Pop Art quotation in this minimal art gesture at an urban scale. Fourth rule of the box: One can make boxes that are not just efficient reductions, deformed, and grandly empty, but also assertively about themselves as autonomous expressions of the art of making form as shelter.

At the very edges of the box, in more ways than one, there is its disintegration into materials that deny its coherence. Thus the fifth and last rule of the box is that it always tends towards its own dissolution. This used to be what German architects did with glass, as Hascher Jehle proved in such a composed manner in the Stuttgart Kunstmuseum just a few years ago. Now this work is being carried out in subtler and yet more assertive materials. Wandel Hoefer Lorch, who had previously twisted the Dresden synagogue off of its square plinth, this last year designed the Jewish Center in Munich as what appears to be a classic concrete box, but turns out to be a complex assembly of loose-fitted stones with no base, top or any other indication that they have not just been piled one on top of the other. From behind this accumulation of building blocks, a glass-clad tower behind which a wood block shimmers rises in uncertain and ethereal elegance.

These are only the most expressive and noteworthy boxes. All over Germany, as well as Switzerland, Austria and many other countries, simpler boxes contain houses and apartments, gymnasia and libraries, offices and schools. The box is everywhere. It is good to remember that in many ways there is nothing particularly innovative about the new German box. In it, architects are elaborating strategies developed during the 1990s, mainly in England and Switzerland, while at the same time operating within the limited field provided for individual expression in situations in which reuse and efficiency are the most important qualities clients and authorities ask for. One could even speculate that the box is a metaphor for a society retreating into itself, into the safety of the suburban home with its controlled air and light and its television and internet, or behind walls of xenophobic traditions. Or one could point to the fact that everything is becoming a box, from our economically and engineering optimized houses and offices to the standard shipping containers that have influenced the size and design of everything from cartons stacked inside of them to the height of overpasses underneath which they must pass.

Whatever the cause of their popularity, boxes are becoming the lingua franca of the Germanic speaking countries. If nothing else, they stand for a newfound realism. After an era in which the past and its forms dominated German architecture, and in a period in which fluid global forms alight everywhere, these boxes attempt to frame and fix the here and now, however contingent that may be. Perhaps they are building blocks for something better in coming years.

Aaron Betsky ist Direktor des Cincinnati Art Museum. Davor leitete er das NAI und war Kurator für Architektur, Design und Digital Projects am San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Als ausgebildeter Architekt hat er rund ein Dutzend Bücher über Architektur und Design verfasst, zuletzt »False Flats: Why Dutch Design Is So Good« (2004).

Teilen:

Trockene Socken

Trockene Socken